This page is still in progress.

Interpretations of Quantum Mechanics

«New interpretations appear every year. None ever disappear.»

Very little is known about quantum mechanics besides its formalism and that it works (it describes the world around us) but much has been written about it.[1] For many, what we know is more than enough. This is known as the shut up and calculate school. Although nobody is sure who the headmaster is,[2] the school definitely exists. Others are not satisfied and would like to have, at least, answers such as:

- Is the world local or nonlocal?

- Is the world deterministic or probabilistic?

- Is there even a "world"? (elements of reality)

- Is the observer special? Are we special?

- Where is the "shifty split" and what does it split?[3]

The schism occurred with Born "interpreting" Schrödinger's wavefunction as a probability amplitude, thus bringing a dichotomy between what is "real" and what is physical (what Bell would later call the "beable"). Particular pivotal problems to make sense of the theory are the double slit experiment, the delayed choice experiment, the EPR paradox and, more recently, Wigner's friends. Interpretations should satisfactorily explain all those, which is no easy task since they present different conundrum of the quantum difficulties. Various authors have singled out various experiments as embodying the mysteries of quantum mechanics, e.g.,

[the double slit experiment is] «a phenomenon which is impossible […] to explain in any classical way, and which has in it the heart of quantum mechanics. In reality, it contains the only mystery.»

— The Feynman Lectures of Physics, Vol. 3.

In The Character of Physical Laws, Feynman would further comment (Chap. 6) «Any other situation in quantum mechanics, it turns out, can always be explained by saying, 'You remember the case of the experiment with the two holes? It's the same thing'.» This, however, seems to make nonlocality less troublesome. It also fails to grasp what happens with Wigner's friends.

Providing an alternative starting point, or theory, to address satisfactorily such questions pauses the problem of quantum foundations. The main difficulty of this delicate question is that all competing interpretations, even when they differ wildly, cannot usually be discriminated through the prism of experiments, thus placing the point out of reach of the scientific method. This was the situation during the famed Einstein and Bohr debates, which appeared to be beyond the scope of science, until Bell brought them back to mainstream physics by formulating a no-go theorem which would settle the question in a laboratory: the epitome of the scientific method. Interpretation of quantum mechanics has remained for a long time in the pure philosophical realm but there is hope, e.g., with experimental metaphysics, that they could eventually yield to the empirical method.

In the meantime, one possible approach to such problems which present no way towards their resolution, is to envision all possible alternatives. We do not know which one is correct, but we know that—being imaginative and systematic enough—we will have come to toy with the actual one. Sherlock Holmes would proceed to remove what is impossible to single out what is true, but his quantum counterpart would oppose to that that while

Sherlock Holmes observed that once you have eliminated the impossible then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the answer. I, however, do not like to eliminate the impossible.

A recurrent clue from the various formulations is that something which is not measured, needs not have a value anyway. This brings the central question of realism. Are scientific observations caused by some physical (objective) reality whose existence is independent of human observers? If that is the case, one still needs to grapple with what Einstein called the “spooky action at a distance.” This is a topic which has been much debated by many authors and there exists a huge literature on the topic, see for instance [4].

In the following, we give an overview of the main interpretations.

Path integrals

This could be called the first interpretation, since Feynman's path integral formalism[5] came after the two independent approaches to quantum mechanics (that of Schrödinger and Heisenberg) proved to be different versions of the same thing. Initially, there was no attempt at an interpretation, it just happened that various people found various way to formulate the theory. Feynman was the first to provide an alternative way to look at what was already known, not adding any new result, just a different viewpoint. Hence the first "interpretation". Although this was not the goal of Feynman, this can be used to extract some understanding or underlying picture of what is going on. In this case, it suggests that everything happens simultaneously and interferences lead to the emergence of what is actually measured.

Hugh Everett III's many-words

This is by far the most exotic interpretation despite also being the simplest and most devoid of superfluous assumptions, thus passing Occam's razor test. In fact, according to DeWitt, it is the only formalism «that takes the mathematical formalism as it stands, without adding anything to it, and that at the same time assumes that this formalism provides a complete description of quantum phenomena.»[6] It postulates that there is a full (total, universal) wavefunction of the universe,[7] which obeys Schrödinger's equation, thus being irreversible and deterministic and not involving any measurement, let alone collapse, for a local description of objectively real objects! All those famous problems of quantum mechanics are removed by a painfully obvious—and, what's more, even natural—remedy: the observer is included as part of the physical system under study, to be treated within the theory exactly on the same footing as the rest of the environment. Everything is quantum: there is no cut between the classical macroscopic world and the quantum microscopic one, no cut between an atom and a conscious observer. And why not? Are we not subject to Newton's equations of motion? Why would we escape Schrödinger's? It is worth repeating that it enjoys all the attributes that Einstein had deemed necessary for a physical theory: it is realist, deterministic and local.

This comes at the price, though, that all the possible outcomes of experiments are realized as part of this giant wavefunction of all possibilities, in which we (as observers) coexist in as many alternate realities (or parallel universes) as needed to satisfy unitary evolution. This did not please everybody.

A typical QM measurement, such as that of a spin component in the Stern–Gerlach experiment, is a local and very low energy event. It is not credible that the measurement could have the huge cosmological effect of bifurcating the universe.

When I first heard of the world-splitting assumed in the MWI, I went back to Hugh Everett’s paper to see if he had really said anything so absurd.

"what is most difficult in the Everett interpretation is to understand exactly what one does not understand." Indeed, it may look simple and attractive at first sight, but turns out to be as difficult to defend as to attack.

Everett sometimes referred to his own many-worlds approach as the "pure wave theory", removing the necessity for everything else (particles, collapses, observers, measurement, etc.) The basic idea is that of relative states: the observer becomes relative to his observation. This is why various observations drag their respective observers in their own reality. The features of Copenhagen arise when see from within: «the formal theory is objectively continuous and causal, while subjectively discontinuous and probabilistic» (Everett). It does achieve some striking results, such as deriving complementarity,[8] but also comes with some complications, for instance the derivation of Born's rule for deriving probabilities from the wavefunction, is natural enough for a maximally entangled state, each observer within his branch finding his relative states, almost all the time (in the probabilistic sense of "almost"), in agreement with quantum mechanics due to the branching, but this breaks down for other probabilities, as the branching is in two, not in fractions of the probability amplitudes.[9] The details of an otherwise simple and straightforward (albeit far-reaching) idea require detailed attention to make sense of the theory.

Proponents include David Deutsch, who came up with the idea of a quantum computer based on his belief that universes were indeed splitting.[10] An early supporter was Wheeler, the PhD advisor of Everett, so much so that he even was initially counted as one of its developers, although he later personally distanced himself from the theory.[11] He wrote an "assessment" of the theory[8] to accompany Everett's paper. This is a short and nice paper, with little formalism and defending the approach.

Opponents include L. Ballentine, A. Peres, R. Penrose, J. Bell[12] and almost everybody who studied the problem in detail. Opposition ranges from rabid (as is the case of Rosenfeld who thought Everett was stupid) to moderate acceptation (e.g., Bell, who thinks this is an inferior version of Bohm's theory).

Links & Further reading

- 🕮The Everett Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics: Collected Works 1955-1980 with Commentary. Jeffrey A. Barrett and Peter Byrne. Princeton University Press, 2012. [ISBN: 978-0691145075] Probably the best source as containing Everett's papers (including the two theses) plus comments and contextualization.

- 🕮The Many Worlds of Hugh Everett III: Multiple Universes, Mutual Assured Destruction, and the Meltdown of a Nuclear Family. Peter Byrne. Oxford University Press, 2013. [ISBN: 978-0199659241] Mainly biographical.

- Quantum mechanics and reality. B. DeWitt in Physics Today 23:30 (1970). This is the paper that popularized the theory. Comments and replies (by DeWitt) can be found in Ref. [6].

- The origin of the Everettian heresy. S. Osnaghi, F. Freitas and O. Freire in Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. B 40:97 (2009). On the historical early developments of the theory.

- Everettian Quantum Mechanics on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Everett's son (Mark) on Nova. Material include Everett's PhD thesis.

Pilot wave

This theory, first proposed by De Broglie and then later extended by Bohm[13][14] (it is also popularly known as Bohm's pilot wave or Bohmian mechanics) is the best illustration of an interpretation of quantum mechanics, in that it is fully equivalent as far as the final results go, but in complete opposition regarding what is actually going on.

The Bohmian version posits that an underlying wave (which follows Schrödinger's equation) guides physical particles, the latter being well-defined in terms of their positions and velocities in 3D space, like classical particles. Given that the particles' behaviour is piloted by the wave, which is itself nonlocal and, this time, in the configuration space (of very high dimensions), albeit deterministic, this theory thus retains all the wonders of quantum mechanics (with which it agrees on all results, remember). It is, therefore, a matter of taste whether to abide by this version which "solves" problems such as wave or particle (it is both) and which slit the particle went through (this is not observer-dependent anymore but is well-defined as the theory is both realistic and objective, particles being physical objects). It also gets rid of the measurement problem and the wavefunction collapse. Since it is deterministic, if one would know the initial condition perfectly, one would know where the particle would eventually end up. The lack of knowledge of the initial condition gives rise to the probabilistic aspect, just like in classical mechanics, except that the wavefunction determines both such an initial condition as well as the quantum potential, which drives the particles, so tightening one's knowledge would alter the fate of the particles. The wavefunction itself, and not the particles, rules the dynamical evolution of the system. Crucially, the particles do not act back onto the wavefunction, and are thus mere realization of the scenario acted by the wavefunction. Although there is only one wavefunction, which never collapses, this dual relationship in fact allows to derive the collapse of the wavefunction, to retain only the "branches" inhabited with particles, so that the possibilities not realized carry on an empty evolution in a ghostly fashion. This makes a direct link with Everett's multiverses. Bohm's theory is of the hidden-variables type, the hidden variables being, funnily, the particles themselves! Its main problem is that, being intrinsically nonlocal and ontic (i.e., something real is nonlocal), it makes it difficult to reconcile with relativity, both special, but also quantum field theory and general relativity.

There are various ways to formulate the theory.

Bohm rewrites Schrödinger's equation in a way that gives rise to a quantum potential $Q$ (proportional to~$\hbar$):

$$Q=-{\hbar^2\over 2m}{\nabla^2 R\over R}$$

where $R$ is the (real-valued) modulus of the wavefunction $\psi=R\exp(i S/\hbar)$. Schrödinger's equation applied to this decomposition yields

$$\partial_tS+{(\nabla S)^2\over 2m}+V+Q=0$$

with $V$ the (physical) potential, and

$$\partial_tP+\nabla\left(P{\nabla S\over m}\right)=0$$

where $P\equiv R^2=\psi^*\psi$.

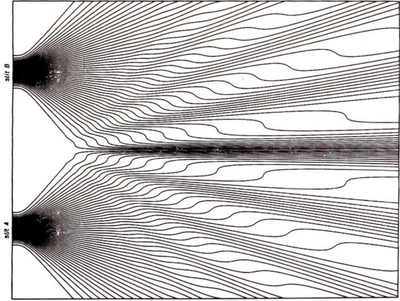

Philippidis et al. studied the quantum potential for the two-slits experiment[15] and produced the now-famous figure actually showing the trajectories of the individual particles, interfering as waves:

This, remarkably, resembles very much the trajectories reconstructed through weak measurements by Kocsis et al.[16] and other works brought even stronger support.[17]

Interestingly, Einstein discussed a "Führungsfeld" (guiding field) for photons, in terms of the electromagnetic field, to account for his revival of the particle-theory of light, even before quantum mechanics itself, and also worked out a quantum version.[18] In a letter to Born, he observed that Bohm's solution seemed "too cheap". He probably did not like the embedded nonlocality, but would have he lived enough to accept its inescapability (post-Bell), no doubt that he would have embraced Bohm's (nonlocal) realistic version.

The interesting feature of Bohm's theory is that it shows that physics is local in configuration space, but not necessarily in ordinary space. That suggests that real space is a projection of a broader reality.

A dialogue covers the basics in Ref. [19]. See also the introduction by Goldstein.[20]

Besides D. Bohm and L. de Broglie, proponents include Bell and others (S. Goldstein, T. Maudlin·, J. Bricmont[21], etc.)

Opponents include Heisenberg (who called it a "superfluous 'ideological superstructure'"), Englert, Scully et al. who described "surreal" trajectories, would the theory be true[22] (as it seems to be[17]).

QBism

Quantum Bayesianism (QBism), pronounced, but not understood as, "cubism" (although QBists like to toy with the connection), takes the opposite view of interpretations that seek to remove the observer from the picture, by asserting instead that predictions of the theory must be formulated and understood from the perspective of a user of this theory. This is called the "operational theory".[23] QBism makes the reasonable proposition that the wavefunction is not something real or physical, but describes our knowledge of the possible outcomes of a measurement. As such, it is an example (and possibly the main one) of a broad school of information-interpretation of quantum mechanics, falling in the class of "epistemic" descriptions (regarding "what we know", as opposed to "ontic", regarding "what there is"). It extends to the quantum realm the Bayesian school of probabilities. This was impulsed by Jaynes, who was both an ardent proponent of the latter as well as a proficient quantum physicist:

our present QM formalism is not purely epistemological; it is a peculiar mixture describing in part realities of Nature, in part incomplete human information about Nature—all scrambled up by Heisenberg and Bohr into an omelette that nobody has seen how to unscramble. Yet we think that the unscrambling is a prerequisite for any further advance in basic physical theory. For, if we cannot separate the subjective and objective aspects of the formalism, we cannot know what we are talking about; it is just that simple. So we want to speculate on the proper tools to do this.

This program was developed as QBism by Christopher Fuchs (who introduced the term) et al. (historically, first with Carlton Caves and Rüdiger Schack[25]). It can basically be seen as a modern (and less philosophical) version of the Copenhagen interpretation, although QBists would refute such a qualification. It is interesting, and possibly relevant, to note that classical probability itself encountered problems of interpretations, with various views contending whether i) this describes objective reality (propensity school), ii) is the result of some sampling or (in our language) measuring of the system (frequentist school) or iii) is the quantification of one's knowledge (or lack of it) of the system (Bayesian school). QBism, as the name indicates, falls in the last category. The collapse of the wavefunction is then nothing more than the acquisition of the knowledge of what was previously unknown. This restores locality as the wavefunction does not describe real objects, but merely one's knowledge.[26] Then, quantum states become a representation of (subjective) information:[27]

One of the things that sets QBism apart from the other interpretations is its reliance on the technical details of quantum information to amplify Feynman’s point—that the modification of the probability calculus in quantum theory indicates that something new is created in the universe with each quantum measurement.

— Quantum foundations. D. P. DiVincenzo and C. A. Fuchs in Physics Today 72:50 (2019).

QBist speak of an 'agent' to describe whoever is tackling their knowledge of whatever they "experience". 'Experience' is another keyword that is a bit unfortunate given its common use since Galileo and its quite precise meaning in QBism of the process through which the 'agent' is refining their "knowledge". In fact "knowledge" is not a QBist term since knowledge is about facts and QBism is about probabilities. At any rate, since an agent is always local, his experience also is: «Quantum correlations, by their very nature, refer only to time-like separated events: the acquisition of experiences by any single agent. Quantum mechanics, in the QBist interpretation, cannot assign correlations, spooky or otherwise, to space-like separated events, since they cannot be experienced by any single agent. Quantum mechanics is thus explicitly local in the QBist interpretation. And that’s all there is to it.»[26] Consequently, various observers may have different wavefunctions to describe the same object.

A drawback of these interpretations is that if the wavefunction is a reflection of one's knowledge, then it is incomplete and does not capture the deeper, underlying element of reality:

Assume that, indeed, $\vert\Psi\rangle$ is affected by an imperfect knowledge of the system; is it then not natural to expect that a better description should exist, at least in principle? If so, what would be this deeper and more precise description of the reality?

Another criticism is that QBism is sollipsist, i.e., considers a reality that exists only in one's mind. If solipsism has a place in science (it has one in philosophy), it seems that QBist would be the best receptacle for it, but QBists strongly refute what they perceive as an accusation and opponents see it as a considerable weakness or even flaw indeed.

Interesting popular accounts include Refs. [28] (with interesting anecdotes on Fuchs).

The leading figure of QBism is Christopher Fuchs. Advocates include David Mermin[3] and Eric Cavalcanti. Opponents include Ballentine,[29] Mateus Araújo[2], M. Nauenberg,[30] etc.

Consistent histories

Also known as "decoherent histories", it was first proposed by R. B. Griffiths[31] and shortly after by R. Omnès.[32] It was also studied by M. Gell-Mann and J. B. Hartle.

It regards quantum mechanics as intrinsically probabilistic, and substitutes the deterministic wavefunction (still used for computational purposes) for probable histories of the observables, which are possible scenarios of what could have happened, generalizing for that purpose Born's rule so that entire sequences of events can be attributed probabilities. It provides a realistic and objective interpretation with no nonlocal (action at a distance) effects. It also flushes the mysteries of quantum mechanics down to single-particle non-commuting observables, or the principle of complementarity. In this sense, the theory has been described as "Copenhagen done right". The EPR paradox, for instance, is resolved by attributing settled correlations from the start, with all various possibilities consisting of coherent histories, removing the need of an observer or of a measurement.[33] A "weakness" of the theory is that it does not settle which set of histories actually happen, only those which can happen. Histories are "consistent" precisely because there can be "quantum incompatibility" which rule out certain alternatives. It also does not settle the problem of the complementarity principle for a single particle, which cannot have a well-defined value for incompatible observables.

Griffiths and Omnès wrote an introductory piece, in which they write:

The central idea is that the rules that govern how quantum beables relate to each other, and how they can be combined to form sensible descriptions of the world, are rather different from what one finds in classical physics

The theory is also introduced by Goldstein.[34]

Quantum Decoherence

This theory, by Wojciech H. Zurek, is independent from the "decoherent histories" of Griffiths & Omnès above (although for a macroscopic system, the latter justify the so-called consistency of families of histories central to their interpretation with Zurek's decoherence). It explains the act of observation from the environment, which acts as an effective observer, thereby effectively making a model of what constitutes "observation" in quantum mechanics.

Relational quantum mechanic

Superdeterminism

Superdeterminism is the term used by Bell to describe the more accurately termed assumption of "Statistical Independence", namely, that the measurement itself is independent of what the detector is set to measure, that is, there is no bias from the detector because it was set to measure one observable rather than another, or, in more quantum mechanical terms, the state itself cannot be prepared independently of how the detector is set up. In equations, this means that the distribution of hidden variables is independent of the measurement settings, i.e., $\rho(\lambda|xy)\neq\rho(\lambda)$ where $\lambda$ is the hidden variable, $x$ and $y$ the detectors configurations and $\rho$ the probability density. Failure to be the case somehow means that the hidden variables do not act the same for a given configuration of the detector, i.e., the detector and the object to be measured are correlated, and since this assumes the theory is deterministic (superdeterminism without determinism would be useless), that suggests (although does not imply) that an agent has "prepared" or "set up" such correlations. For this reason, the vocabulary of "conspiracy" often pops up when discussing the violation of this assumption. A sharp look at the concept arose as early as 1976 in a critical discussion of Bell's definitions of locality and realism:

In any scientific experiment in which two or more variables are supposed to be randomly selected, one can always conjecture that some factor in the overlap of the backwards light cones has controlled the presumably random choices. But, we maintain, skepticism of this sort will essentially dismiss all results of scientific experimentation. Unless we proceed under the assumption that hidden conspiracies of this sort do not occur, we have abandoned in advance the whole enterprise of discovering the laws of nature by experimentation.

Bell called that superdeterminism in a way that implies that this basically removes free choice in the sense that the result is already determined or conditioned ahead of its fair (or independent) measurement. One is not entirely free to decide what to measure in the sense that what will be measured is biased from the outset.[35] This restricts the type of experiment one can conduct, thereby solving the EPR paradox by asserting that the choice of measurement was settled before the measurement itself. On the other hand, that also pauses a lot of problems regarding how to conduct experiments, since one has to worry on the detector/detected relationships. It becomes unclear how to design an experiment since one has to assume the result may depend on what we decide to measure.

I see superdeterminism as having roughly the same scientific merit as creationism. Indeed, superdeterminism and creationism both say that the whole observed world is, in a certain sense, a lie and an illusion (while denying that they say this). They both consider this an acceptable price to pay in order to preserve some specific belief that most of us would say was undermined by the progress of science. For the creationist, God planted the fossils into the ground to confound the paleontologists. For the superdeterminist, the initial conditions, or the failure of Statistical Independence, or the global trajectory-selecting principle, or whatever the hell else you want to call it, planted the random numbers into our brains and our computers to confound the quantum physicists. Only one of these hypotheses is rooted in ancient scripture, but they both do exactly the same sort of violence to a rational understanding of the world.

The assumption is so natural in classical physics, and so necessary to make sense of the results (which otherwise can be biased to obtain meaningless results), that superdeterminism has been ruled out until the situation became so desperate that some people started to take it seriously. If one can look beyond the unfortunate terminology and accept the reasonable assumption that quantum physics may involve bizarre concepts such as not obeying statistical independence, superdeterminism would actually be an effective remedy to many headaches of interpretation. In fact, Bohmian mechanics does involve a bit of superdeterminism in the way the wavefunction determines the quantum potential, itself crucial in bringing the system towards the detector.

For a variety of reasons, many physicists think Superdeterminism is a non-starter. For example, they argue that Superdeterminism would turn experimenters into mindless zombies, unable to configure their experimental apparatuses freely.

— Rethinking Superdeterminism. S. Hossenfelder and T. Palmer in Front. Phys. 8:1 (2020).

Proponents include G. 't Hooft, T. Palmer,[36] S. Hossenfelder, etc. Opponents are many, with fierce outspeaking ones including A. Zeilinger, T. Maudlin, S. Aaronson,[37] Mateus Araújo,[38] N. Gisin, etc. On this matter, the last words can go to the defense:

Attempts to develop models which violate (1) [statistical independence] do not justify the derision from a number of researchers in the quantum foundations community over the years. Not least, Bell himself did not treat the possible violation of (1) with derision and accepted that seemingly reasonable ideas about the properties of physical randomisers might be wrong—for the purposes at hand.

Links

- Does Superdeterminism save Quantum Mechanics? Or does it kill free will and destroy science? by Hossenfelder.

Enlightened ones

Besides or beyond the "agnostic" approach of not worrying about the interpretation because this is either futile or unnecessary, one can also find the view that it is actually not needed at all, since there is no problem of interpretation in the first place and everything is accounted for by the theory, since it works in producing what it aims to describe.[39]

Quantum Theory Needs No ‘Interpretation’. C. A. Fuchs and A. Peres in Physics Today 53:70 (2000).

Still others

- Time-symmetric theories: putting past and future on an equal footing. Proposed by Schottky in 1921.

- Transactional interpretation: both the field $\psi$ and its complex conjugage $\psi^*$ are real (physical) objects which describe a "possibility wave" from the source to the receiver and vice-versa, whose mutual interaction realizes a transaction.

- Quantum logic: positing that logic as we know it is not suitable to describe the quantum regime. Possibly related to Feynman's negative probabilities.

- Quantum Darwinism: a well-packaged and wrapped-up version of decoherence.

- Stochastic quantum mechanics: Newton's equations with stochastic terms lead to Schrödinger's equation.[40]

Not all interpretations are exactly equivalent to orthodox (Copenhagen) version. For instance, Spontaneous Localization predicts small energy increases with time, but too small to be detected.

Still, still others

Modal interpretations of quantum theory, Many-minds interpretation, Quantum mysticism, magic, a prank by God, etc.

Copenhagen Interpretation

We put it last while it ranks first from historical, practical and didactic points of view. Impulsed by Bohr (mainly) and Heisenberg (in his shadow, though not without disagreements), it is also the oldest formulation of some form of interpretation (in the mid-20s). It is in fact so predominant as to be known as the "orthodox" view of quantum mechanics! It relies chiefly on the principle of complementarity, which states that not everything can be known about a quantum object. The observation is irreversible in that it causes a collapse of the wavefunction. A tenet of this interpretation is the schism between the quantum (microscopic) and classical (macroscopic) words. The observation becomes central to the theory as a way to bring the quantum system, but from outside of it, to our classical senses (and thus in terms of classical concepts), where it does not belong, having intrinsic incompatibilities with it, such as complementarity. The interpretation was much discussed at the 5th Solvay conference.[41] Its proponents include Bohr, whose paper replying to EPR (with the same title)[42] can be regarded as the Copenhagen-interpretation paper, and also von Neumann, who formulated the Mathematical axioms of the theory. Its detractors include Einstein and everybody siding with any of the alternative interpretations above.

If that were so then physics could only claim the interest of shopkeepers and engineers; the whole thing would be a wretched bungle.

— Einstein, In a letter to Schrödinger [3]

No reasonable definition of reality could be expected to permit this.

The point is no longer that quantum mechanics is an extraordinarily (and for Einstein, unacceptably) peculiar theory, but that the world is an extraordinarily peculiar place.

If there is spooky action at a distance, then, like other spooks, it is absolutely useless except for its effect, benign or otherwise, on our state of mind.

In speaking of the adherents of this interpretation, it is important to distinguish the active adherents from the rest, and to realize that even most textbook authors are not included among the former. If a poll were conducted among physicists, the majority would profess membership in the conventionalist camp, just as most Americans would claim to believe in the Bill of Rights, whether they had ever read it or not.

The name comes from Heisenberg[11] despite his personal reluctance to complementarity. The reason might be as an atonement following his WWII break-up with Bohr.

M. Jammer, The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics 共McGraw–Hill, New York, 1966兲; second edition 共1989兲.

Proponents include Bohr himself, not quite Heisenberg, interestingly, but rather fanatics like L. Rosenfeld who commented as follows on the Copenhagen interpretation:

there has never been any such thing and I hope there will never be. The only distinction is between physicists who understand quantum mechanics and those who do not.

One should also include as proponents W. Pauli, A. Peres, A. Wheeler, von Weizsäcker, R. Peierls...

Links

- From the Wikipedia.

- Feynman speaking about it (and part 2)

- Other links: [4]

References

- ↑ Resource letter IQM-2: Foundations of quantum mechanics since the Bell inequalities. L. E. Ballentine in Am. J. Phys. 55:785 (1987).

- ↑ Could Feynman Have Said This?. N. D. Mermin in Physics Today 57:10 (2004).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Quantum mechanics: Fixing the shifty split. N. D. Mermin in Physics Today 65:8 (2012).

- ↑ Do we really understand quantum mechanics? Strange correlations, paradoxes and theorems. F. Lalöe in Am. J. Phys. 69:655 (2001).

- ↑ Space-Time Approach to Non-Relativistic Quantum Mechanics. R. P. Feynman in Rev. Mod. Phys. 20:367 (1948).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Quantum-mechanics debate. L. E. Ballentine, P. Pearle, E. H. Walker, M. Sachs, T. Koga, J. Gerver and B. DeWitt in Physics Today 24:36 (1971).

- ↑ "Relative State" Formulation of Quantum Mechanics. H. Everett III in Rev. Mod. Phys. 29:454 (1957).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Assessment of Everett's "Relative State" Formulation of Quantum Theory. J. A. Wheeler in Rev. Mod. Phys. 29:463 (1957).

- ↑ 🕮Making Sense of Quantum Mechanics. Jean Bricmont. Springer, 2013. [ISBN: 978-3319258874]

- ↑ The structure of the multiverse. D. Deutsch in Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 458:2911 (2002).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 The origin of the Everettian heresy. S. Osnaghi, F. Freitas and O. Freire in Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. B 40:97 (2009).

- ↑ The Measurement Theory of Everett and De Broglie’s Pilot Wave. J. S. Bell in Quantum Mechanics, Determinism, Causality and Particles 1:11 (1976).

- ↑ A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of "Hidden" Variables. I. D. Bohm in Phys. Rev. 85:166 (1952).

- ↑ A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of "Hidden" Variables. II. D. Bohm in Phys. Rev. 85:180 (1952).

- ↑ Quantum interference and the quantum potential. C. Philippidis, C. Dewdney and B. J. Hiley in Nuov. Cim. B 52:15 (1979).

- ↑ Observing the Average Trajectories of Single Photons in a Two-Slit Interferometer. S. Kocsis, B. Braverman, S. Ravets, M. J. Stevens, R. P. Mirin, L. K. Shalm and A. M. Steinberg in Science 332:1170 (2011).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Experimental nonlocal and surreal Bohmian trajectories. D. H. Mahler, L. Rozema, K. Fisher, L. Vermeyden, K. J. Resch, H. M. Wiseman and A. Steinberg in Science Advances 2:e1501466 (2016).

- ↑ What's Wrong with Einstein's 1927 Hidden-Variable Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics?. P. Holland in Found. Phys. 35:177 (2005).

- ↑ Understanding Bohmian mechanics: A dialogue. R. Tumulka in Am. J. Phys. 72:1220 (2004).

- ↑ Quantum Theory without Observers-Part Two. S. Goldstein in Physics Today 51:38 (1998).

- ↑ Diagnosing the Trouble with Quantum Mechanics. J. Bricmont and S. Goldstein in J. Stat. Phys. 175:690 (2018).

- ↑ Surrealistic Bohm Trajectories. B.-G. Englert, M. O. Scully, G. Süssmann and H. Walther in Zeitschrift für Naturforschung A 47:1175 (1992).

- ↑ The View from a Wigner Bubble. E. G. Cavalcanti in Found. Phys. 51:39 (2021).

- ↑ Complexity, Entropy and the Physics of Information. E. T. Jaynes in 🕮Complexity, Entropy and the Physics of Information. Wojciech H. Zurek (Ed.) Westview Press, 1990. [ISBN: 978-0201515060]

.

.

- ↑ Quantum probabilities as Bayesian probabilities. C. M. Caves, C. A. Fuchs and R. Schack in Phys. Rev. A 65:022305 (2002).

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 An introduction to QBism with an application to the locality of quantum mechanics. C. A. Fuchs, N. D. Mermin and R. Schack in Am. J. Phys. 82:749 (2014).

- ↑ Quantum-Bayesian coherence. C. Fuchs and R. Schack in Rev. Mod. Phys. 85:1693 (2013).

- ↑ Quantum Weirdness? It's All in Your Mind. H. C. v. Baeyer in Sci. Am. 308:46 (2013).

- ↑ Reviews of quantum foundations. D. Ballentine in Physics Today 73:11 (2020).

- ↑ QBism and locality in quantum mechanics. M. Nauenberg in Am. J. Phys. 83:197 (2015).

- ↑ Consistent histories and the interpretation of quantum mechanics. R. B. Griffiths in J. Stat. Phys. 36:219 (1984).

- ↑ Logical reformulation of quantum mechanics. I. Foundations. R. Omnès in J. Stat. Phys. 53:893 (1988).

- ↑ Correlations in separated quantum systems: A consistent history analysis of the EPR problem. R. B. Griffiths in Am. J. Phys. 55:11 (1987).

- ↑ Quantum Theory without Observers-Part One. S. Goldstein in Physics Today 51:42 (1998).

- ↑ Free Variables and Local Causality. J. S. Bell in Epistemol. Lett. 15:79 (1977).

- ↑ Superdeterminism without Conspiracy. T. Palmer in Universe 10:47 (2024).

- ↑ On tardigrades, superdeterminism, and the struggle for sanity on Shtetl-Optimized.

- ↑ Superdeterminism is unscientific on More Quantum.

- ↑ The scandal of quantum mechanics. N. G. van Kampen in Am. J. Phys. 76:989 (2008).

- ↑ Derivation of the Schrödinger Equation from Newtonian Mechanics. E. Nelson in Phys. Rev. 150:1079 (1966).

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality be Considered Complete?. N. Bohr in Phys. Rev. 48:696 (1935).

- ↑ Still more quantum mechanics. G. L. Trigg, M. Hammerton, Jr R. Hobart Ellis, R. Goldston and H. Schmidt in Physics Today 24:11 (1971).

- ↑ Role of the Observer in Quantum Theory. A. Shimony in Physics Today 31:755 (1963).

More references

- Quantum (Un)speakables: From Bell to Quantum Information, Ed. by R.A. Bertlmann and A. Zeilinger.

- Ball's Beyond Weird

- Ananthaswamy's Through Two Doors at Once