Continuous emission spectra from planetary nebula provide an illustrative case for historians of science of niche discoveries which attracted little attention, despite their possible extremely fundamental nature and needed pursuit.

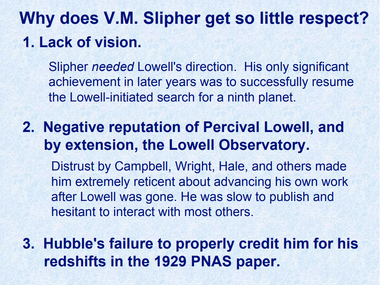

Meet Vesto Slipher, who dodged all opportunities at becoming famous, including the discovery of Pluto, predicted by his former boss and confirmed by his employee when Vesto took over. His biggest claim to missed recognition, however, is his pioneering observation of, and comments about, the expansion of the Universe, which he had established a decade before the shaking report that would make Einstein recognize the biggest blunder of his life. The empirical finding is largely attributed to Hubble, whose recognition has been such to have an eponymous telescope put in the sky. Many of the great things that Hubble did have been previously discovered by this shy, disregarded and lesser-known scientist, whose name I challenge you to remember tomorrow. Here is the conclusion slide of a tribute to Vesto:

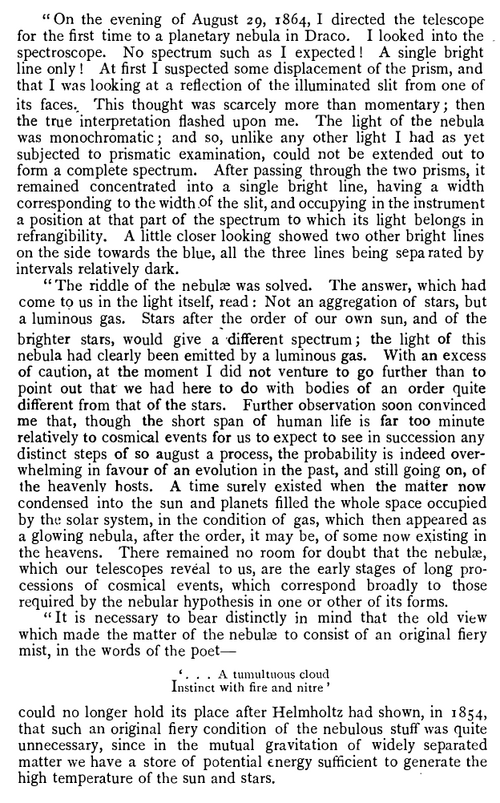

He interests us, for the duration of this text, for his discovery of the continuous spectra of certain gaseous nebulae.[1] It was already known (since Huggins) that nebulae could have spectra that were either continuous or with discrete lines, but the sensation was initially from the discrete lines, revealing that nebulae were gaseous (cosmic dust). The continuous spectrum was thought to have a more prosaic explanation from the added contributions of the many stars composing the nebula. This is how Huggins—the spectroscopist of stars—relates his discovery, as reported by William Watts in his beautiful book An introduction to the study of spectrum analysis:

It was, therefore, for Slipher to rediscover continuous spectra from the one and same nebulous object (not some superposition of disconnected stuff). The observation of such continuous spectra from nebulas was extended and generalized considerably by Hubble[2] a decade later, also about a decade earlier the expansion thing. Slipher's trajectory would be worth all our time, but let us follow the nebulae instead.

Page[3] was the first to worry on continuous spectra in the visible range, which he reported himself for the NGC 7662 planetary nebula, also known as the blue snowball nebula, which is well justified if imaged with sufficiently low resolution:

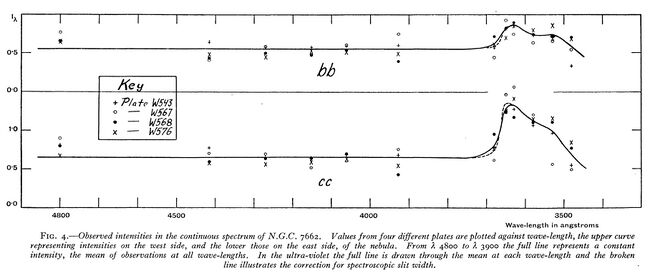

It looks more like a jellyfish otherwise. Here is Page's observation, on both sides of the nebula, of its visible (and UV on the right) spectrum, from four different plates:

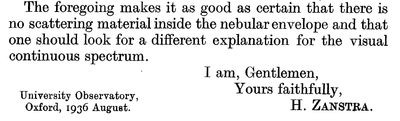

It's constant. Or, in spectroscopic parlance, continuous. Page tried to interpret this feature in terms of previous mechanisms, just brought to the visible window, but he had actually found something more important, since the obvious reasons did not stand against careful scrutiny:[4]

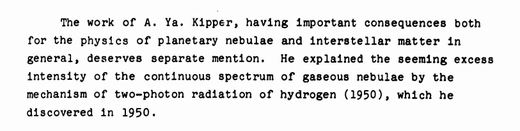

This turned out to be quite of a mystery for decades. This was eventually elucidated with Kipper[5] and Spitzer & Greenstein[6]'s "independent" understanding that this involved two-photon emission. It is unclear how independent were their finding, since the latter knew of the idea from the former, but what exactly the idea was stating is difficult to assess to this day. In their analysis, Spitzer and Greenstein comment that

this process had already been considered [...] more recently by A. Y. Kipper; no details of Kipper’s work are apparently available in this country

This is an understatement. Beyond no details being available, what I found is very confusing material regarding this discovery from Estonia. I could not find the original Kipper text, cited as A.J.U.S.S.R., 27, 321, 1950 by Spitzer & Greenstein, and which seems to be reproduced in a mysterious Israeli project of translating scientific Russian texts (I couldn't find this book online either but one can get it here). What one can find is the particularly enigmatic reference [5], which is part of some strange compilation of abstracts, of the form "O Razvitii Sovetskoi Nauki v E'stonckoi S.S.R." (translating as "On the Development of Soviet Science in the Estonean S.S.R."). This is on p°316 if someone ever finds this source, and more importantly for our historical records, is indeed from 1950. Even Kipper himself, in his later publications, refers to this 1950 text in this way. This is, for instance, the first Reference from "Теория двожного излучения световйҳ квантов для атома водорода":[7]

and this is Ref. 2 from "Он непрерйвном спектре галактическиҳ туманностей":[8]

and when you'd think you've seen it all, you also stumble upon such beauty as the US military, automatically translated versions of Russian scientific works. Look it up for yourself.

In this automatic translation, one finds on page 266 a direct mention and description of the 1950 Kipper "paper" (by G. S. Khromov in the chapter 'Interstellar Matter and Planetary Nebulae'):

There are other papers by Kippers worth one's attention on this matter, but they are more recent,[9] as compared to Spitzer & Greenstein's quite thorough analysis.[6] For historical accuracy, one should also highlight that Spitzer & Greenstein also acknowledge Informal communication$^5$ with Minkowski and Aller, who we previously hid in ellipses, although they had toyed with the idea. But rejected it:

Continuous emission spectra from planetary nebula thus provide us with a cosmic testimony to how obscure and off-the-beaten-track is the pursuit of Science when it does not fall into the limelight, of before it does. Who knows or cares about Vesto, although a genius, about the insights of Page and Zanstra, about the neglected merits of Minkowski and Aller, about the breakthroughs of Kipper, Spitzer & Greenstein? For billions of years, and billions more to come, they did and will keep glowing throughout the immensity of space in a way that underpins all our current knowledge of basic light-matter interactions, yet impinging on the concerns of, and enlightening, less than a select few.

References

- ↑ On the spectrum of the nebula in the Pleiades. V. M. Slipher in Low. Obs. Bull. 2:26 (1912).

- ↑ A general study of diffuse galactic nebulae. E. P. Hubble in Astrophys. J. 56:162 (1922).

- ↑ The Continuous Spectra of Certain Planetary Nebulæ A Photometric Study. T. L. Page in Mon. Notices Royal Astron. Soc. 96:604 (1936).

- ↑ An argument against scattering in planetary nebulae. H. Zanstra in Observatory 59:314 (1936).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sbornik "O Razvitii Sovetskoi Nauki v E'stonckoi S.S.R." (On the Development of Soviet Science in the Estonean S.S.R.). A.Ya. Kipper in Tallin 316 (1950).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Continuous Emission from Planetary Nebulæ. L. Spitzer Jr. and J. L. Greenstein in Ap. J. 114:407 (1951).

- ↑ Teoriya dvojnogo izlucheniya svetovyh kvantov dlya atoma vodoroda (The theory of dual radiation light rays of the hydrogen atom). A. Ya. Kipper in Pub. Tartu Astr. Obs. 32:63 (1952).

- ↑ On nepreryvnom spektre galakticheskih tumannostej (The continuous spectrum of galactic nebulae). A. Ya. Kipper in Pub. Tartu Astr. Obs. 32:327 (1952).

- ↑ The Processes of the Disintegration of Light Quanta and Their Significance in the Physics of Gas Nebulae. A. Ya. Kipper and V. M. Tayt in Probl. Cosmogeny 6:109 (1964).