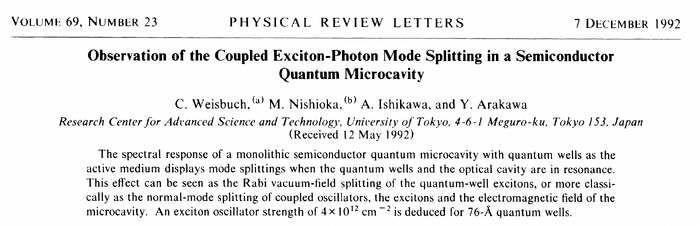

Observation of the coupled exciton-photon mode splitting in a semiconductor quantum microcavity. C. Weisbuch, M. Nishioka, A. Ishikawa and Y. Arakawa in Phys. Rev. Lett. 69:3314 (1992). What the paper says!?

This is the seminal paper for microcavity-polariton physics, although the reported effect (Rabi splitting at resonance) is contrasted against polaritons, which are then understood as the bulk propagation in crystals, as defined by Hopfield:[1]

The dichotomy is complete with the observations that «Although representing the fundamental electromagnetic excitations of 3D crystals, polaritons are not versatile and cannot be tailored at will. The new system (inset of Fig. 1) which we use here should prove much more important in that respect [...]» and, later, that «There is no exciton polariton like in the 3D semiconductor case». This last statement is the most vexing one in the full paper, it describes the fact that excitons are blocked along the quantization axis and thus cannot propagate (as they would in the bulk). This shortsighting is a bit surprising as the Authors highlight that, in contrast to atomic experiments:

In our experiments, excitons can have in-plane wave vectors which allow excitons to couple to oblique FP modes.

They can therefore propagate in-plane, and the 2D-polariton or cavity-polariton picture is compelling, but it is not made. One must understand the offending sentence, however, as "there is no 3D exciton polariton", rather than "there is no polariton, like in 3D" (note the added comma). In a footnote, the Authors indeed emphasize the dimensionality issue by referring to the the transition from 2D excitons to 3D polaritons just discussed by J. Knoester.[2] The Authors got very close to writing in full the direct consequence of what they understood:

It therefore seems surprising that the excitons, which can interact with a continuum of photon modes, should display a Rabi oscillation evidencing the coupling to a single photon mode. However, because of the translational invariance of the crystal in the QW plane, the in-plane exciton wave vector is a good quantum number and must equal that of a photon in an optical transition. Therefore, an optically created exciton will have a well-defined in-plane wave vector, and will only interact with one cavity mode with the same transverse photon wave vector[...]

Namely, they observed 2D-polaritons. Interestingly, Weisbuch was also involved in the previous «most direct evidence of polaritons» (of the conventional, or 3D, type).[3] The connection to polaritons will be made a few months later, in July (1993), in a Cargese school organized by Weisbuch (and E. Burstein). There the new quasiparticle will be called Cavity-Polariton.[4]

The description of the Rabi oscillations nevertheless fits the modern definition of the polariton:

Rabi oscillations can be seen as a coupled-oscillator process, by which resonantly coupled atomic and field oscillators periodically exchange energy. In a mechanical oscillator description, the overall system response yields two split modes corresponding to the normal modes. In an atomic transition language, one considers the system as undergoing a coherent evolution with a photon being absorbed by an atom, which subsequently emits a photon with the same energy and wave vector k, that photon being reabsorbed, and so on.

At the time, the highlight was regarded instead as bringing a QED-counterpart in the solid-state of atomic experiments, which were «so far [...] quite separate»:

Much precaution was taken, even in the abstract, as to what was reported:

This effect can be seen as the Rabi vacuum-field splitting of the quantum-well excitons, or more classically as the normal-mode splitting of coupled oscillators

The observation comes against prior predictions of the difficulty (or impossibility) of observing Rabi oscillations from electron-hole transitions.[5] The benefit of excitons instead of e/h pairs seems to be first appreciated in this paper.

The paper also makes an implicit mention to what would become the polariton laser (without naming it this, especially given the anti-polariton stance of this paper, but referring to «the thresholdless laser») through Ref. [6].

The reference to M. Raizen et al.[7] (Ref. 2 of the paper) is misattributed to R. J. Thompson.

References

- ↑ Theory of the Contribution of Excitons to the Complex Dielectric Constant of Crystals. J. J. Hopfield in Phys. Rev. 112:1555 (1958).

- ↑ Optical dynamics in crystal slabs: Crossover from superradiant excitons to bulk polaritons. J. Knoester in Phys. Rev. Lett. 68:654 (1992).

- ↑ Resonant Brillouin Scattering of Excitonic Polaritons in Gallium Arsenide. R. G. Ulbrich and C. Weisbuch in Phys. Rev. Lett. 38:865 (1977).

- ↑ 🕮Confined Electrons and Photons: New Physics and Applications. Claude Weisbuch and Elias Burstein (Editors). Springer, 1995. [ISBN: 978-1-4613-5807-7]

- ↑ Cavity quantum electrodynamics in quantum well lasers. Y. Yamamoto, S. Machida and G. Björk in Surf. Sci. 267:605 (1992).

- ↑ Modification of spontaneous emission rate in planar dielectric microcavity structures. G. Björk, S. Machida, Y. Yamamoto and K. Igeta in Phys. Rev. A 44:669 (1991).

- ↑ Normal-mode splitting and linewidth averaging for two-state atoms in an optical cavity. M. G. Raizen, R. J. Thompson, R. J. Brecha, H. J. Kimble and H. J. Carmichael in Phys. Rev. Lett. 63:240 (1989).