I discovered Philip Glass in 1992, in my Lycée years (secondary school in France) in a beautifully shaped building that was inspiring for the aspiring scientist.

that was inspiring for the aspiring scientist.

My main grip on science was then through computers. My interest in mathematics and theoretical physics existed but was crippled by lack of a proper feedback. Teachers were outright imbeciles. The only interesting persons I was frequenting (I was at a point-low in my social life) were computers type of people. One was theory oriented, a programmer with interest in cryptography, so in his wake, I got to focus on assembly language rather than pure science. I had met him and his "group" (the Silver Ghosts, demo-makers on Atari ST machines) a few years earlier (in collège). This guy was a stimulating and charismatic figure who appealed a lot to my INTJ character (and who had me realize I was an INTJ by the way). He didn't call himself a programmer but a coder. He also managed to be in touch with other fantastic people, other coders but also artists, musicians, etc., who were all creative, curious, entertaining. When we went to see Jurassic Park on the big screen, there was this scene where Nedry complains "You know anybody who can network eight connection machines and debug two million lines of code?" at which point one of them replied, as if obvious: "Hexa" (this was this guy's codename, because we all had a codename, mine was "Spark" by the way. Later it became "Huho" after Calvin & Hobbes). These guys were cool like that.

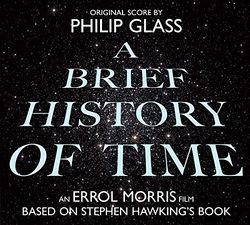

And time went forward. My friend was getting increasingly obsessed with Bruce Schneier, but at some point my infatuation for his topics took a turning point. We were fondly discussing articles in a computer magazine from someone Dave Small who was praising the concept of hackers and comforting our sense of excluded people (he had a piece on surviving school, which is exactly how I felt). One day, he made a story on Feynman (he had made one on Tesla before, the greatest of hackers in his view). I got very excited by the physics described there. And thus I got interested in Physics. It's incredible how school can make interesting things repelling. It's fortunate I first heard of quantum mechanics away from a classroom. The paper on Feynman got me started onto my own "research" (you don't even imagine or probably can't remember the state of the internet by then, which I had, by the way, I was very upfront in the Gaussian tail of early people to get the internet) and I got a grip to Hawking's A Brief History of Time. I've always had this weakness of wanting all the sources, so I got access to the Errol Morris movie as well. That was a long detour, but that's how I discovered Philip Glass.

The movie's opening, the very first second, less than that, the music of Glass, it captured me, it talked to me, it sounded to me the way it does when there is a revelation. The movie is not particularly great, neither is the book, by the way, but the music is outstanding and it accompanied—if not make me develop—my passion for the topic. There's always an amount of romance to any love story, a something that is sometimes unrelated, or tenuously so, to the object of desire. The music of Glass is the romance of my relationship with physics.

When internet grew to be mature, and things like Wikipedia came to existence, and Google took over Alta-Vista, I was then in a position (now a routine for anybody) to look up things. Of course I had gotten grab of some Glass's compositions. My first try was Koyaanisqatsi, and then Einstein on the Beach. It was "okay" but like every second thing in everything, it was a disappointment as compared to the hit of the first encounter. People made fun of the opening of the Einstein opera and I could almost understand that. Glass still became one of my favorite composers. I am an unreserved lover of Les Enfants Terribles (and would like to perform it one day), or of Mad Rush, the play between the wrathful and peaceful Tibetan deities. I regularly listen the Aguas da Amazonia in loops.

But still the soul-gripping composition remained the music of my 15 years old, the soundtrack of the Hawking biography. And even the grown-up internet couldn't help me locate that. It did not appear in the compositions of the author and was nowhere to be found, but in the movie itself. That has always been a frustration for me. His Magnum Opus as I see it, was, apparently, some uncatalogued stuff he did for a documentary. What a bitter disappointment.

So you can imagine my excitement when I discovered that, in April 2015, the original score was released! (the movie is from 1991).

- Then, brothers, it came. O bliss, bliss and heaven, oh it was gorgeousness and georgeosity made flesh.

This is the listing:

| Track | Title | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brief History of Time Title | 1:31 |

| 2 | Mysterious No. 4 | 3:38 |

| 3 | Bombs with Fidelity | 2:24 |

| 4 | Sow, Simple, Sad No. 3 | 3:56 |

| 5 | Mysterious No. 1 | 2:45 |

| 6 | Slow, Simple, Sad No. 4 | 3:59 |

| 7 | Mysterious No. 2 | 2:44 |

| 8 | Hawking-Radiation | 1:44 |

| 9 | Bombs | 2:49 |

| 10 | Dice | 2:13 |

| 11 | Hawking-Radiation with Brass | 1:45 |

| 12 | Climbing the Stairs | 1:25 |

| 13 | End with Strings and Trumpets | 2:19 |

| 14 | Melody in Major | 3:12 |

| 15 | Signature | 2:56 |

| 16 | Utility No. 1 | 3:34 |

| 17 | House | 2:08 |

| 18 | Closing No. 1 | 3:30 |

| 19 | End Credits Arpeggio and Brass | 2:13 |

It is always interesting to read the titles of pieces written after a theme, a sort of musical trahison des images. It is illustrative, for instance, how Vangelis' De Nuremberg à Nuremberg soundtrack for the Rossif documentary (in French) on World War II, indeed a nice composition that fits very well its topic, is nailed to it by bizarre and forbidding titles (Mein Kampf is disagreeable enough so that it would never be used again for another purpose but imagine having to credit Nazi Europa or say that you really like Hitler in Paris or Genocide; thankfully the real good scores have innocuous titles, such as When Soldiers Fight [which should have been "When Soldiers Die", and vice-versa] or De Nuremberg...).

But back to our today's theme. Look at the titles for the compositions: "Mysterious", "Slow, Simple, Sad" or the very danceable "Hawking-Radiation". Is it not already inspiring, melancholic, mysterious, bewildering, uncanny and inviting all at the same time? (pity the end credit is called precisely that). The pieces are short, typically reduced to their simple idea, without the full development to make them complete works. But their subtraction from the public for so long has been very much grieved for. They are, in much respect, the Pensées of Glass: a jolting down of mere ideas, of pure insights, of key themes, of unfinished, maybe better qualified as of incomplete, peeks into the wider picture. Taste that and you can imagine what the big thing is about. And shrill. Maybe the full version is better left unborn even, like Gogol's masterpiece which he had to destroy for fear or confronting to reality the potential he had put on foot. When something is too beautiful, too good to be true, it must belong to some other dimension and better take its place in ours through snippets, because when it's too big, you just can't appreciate the size.