The Children of Gaza and the Last Jew of Vinnitsa

m |

m |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

The victim, first, holding his coat, maybe not to dirty it. His expression is inscrutable. The gaze is both distant and already in the afterlife, at the same time as it seems to anchor onto someone, something, a tree maybe, the roof of his house, more soldiers like those behind him. What is he looking at, like this? The incredulity of being one of us? I like to think he's looking at an Angel that only him can see, being already on the other side, and that his expression is one of embarrassment at having to embrace the divine from such a pathetic entrance: «Sorry». One can feel all the guilt of humanity on his expiating shoulders. Things that cannot be explained can sometimes be evoked in the prose of great authors. This mysterious expression always reminded me of [[Garcia Marquez]]'s opening line to his [[Cien años de soledad]]: <wz tip="«Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.»">«{{onlinequote|Muchos años después, frente al pelotón de fusilamiento, el coronel Aureliano Buendía había de recordar aquella tarde remota en que su padre lo llevó a conocer el hielo.}}»</wz> His smile is tortured, floating between abnegation and acceptation. Maybe he does not believe what is going on, although he has just seen with his own eyes the others preceding him, roll down the pit after being shot. This is all just ''so'' absurd, that surely the frightful misunderstanding will be lifted. I think he is definitely looking at an Angel. Or remembers some suspended eternity once shared with his dad. | The victim, first, holding his coat, maybe not to dirty it. His expression is inscrutable. The gaze is both distant and already in the afterlife, at the same time as it seems to anchor onto someone, something, a tree maybe, the roof of his house, more soldiers like those behind him. What is he looking at, like this? The incredulity of being one of us? I like to think he's looking at an Angel that only him can see, being already on the other side, and that his expression is one of embarrassment at having to embrace the divine from such a pathetic entrance: «Sorry». One can feel all the guilt of humanity on his expiating shoulders. Things that cannot be explained can sometimes be evoked in the prose of great authors. This mysterious expression always reminded me of [[Garcia Marquez]]'s opening line to his [[Cien años de soledad]]: <wz tip="«Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.»">«{{onlinequote|Muchos años después, frente al pelotón de fusilamiento, el coronel Aureliano Buendía había de recordar aquella tarde remota en que su padre lo llevó a conocer el hielo.}}»</wz> His smile is tortured, floating between abnegation and acceptation. Maybe he does not believe what is going on, although he has just seen with his own eyes the others preceding him, roll down the pit after being shot. This is all just ''so'' absurd, that surely the frightful misunderstanding will be lifted. I think he is definitely looking at an Angel. Or remembers some suspended eternity once shared with his dad. | ||

| − | After trying to feel being him, in front of the grave that will punctuate his life, I then try to feel being the soldier about to execute him. His | + | After trying to feel being him, in front of the grave that will punctuate his life, I then try to feel being the soldier about to execute him. His steady, precise position—straddling the precipice which he is about to fill with a human soul—the care in aiming precisely at the centre of the skull, the suspended breathing before pushing the trigger, the delicate concentration as if pondering a tricky task. The whole pose would look natural if he had a balloon to pop at the fair in front of him. It would already be chilling if it was a goose at his feet. But in front is this enigmatic, fathomless, infinitely precious soul who surrendered his fear, his rage and his torments to expose naked his fate to his murderer, becoming immortal together on this one instant that they both did not even live through and that is for us, instead, to spend the rest of our lives with. |

And then the people behind this macabre couple... I always had a fascination for these photos where the victim is placed together with their assassin, side by side. This is the climax of vulgarity. Here the composition goes so far as merging them in the act, more intimately binding themselves together than two lovers. The incongruity becomes Christic. But back to the crowd, to the rest of humanity, to each one of the people behind them. One after the other. With their expression which is the one each of us still has, to this day, when we find ourselves, as [[Dard]] put it, less than the accomplice but more than the witnesses, of the crimes being committed, constantly, all around, by all of us, when they are committed by even the worst of us. | And then the people behind this macabre couple... I always had a fascination for these photos where the victim is placed together with their assassin, side by side. This is the climax of vulgarity. Here the composition goes so far as merging them in the act, more intimately binding themselves together than two lovers. The incongruity becomes Christic. But back to the crowd, to the rest of humanity, to each one of the people behind them. One after the other. With their expression which is the one each of us still has, to this day, when we find ourselves, as [[Dard]] put it, less than the accomplice but more than the witnesses, of the crimes being committed, constantly, all around, by all of us, when they are committed by even the worst of us. | ||

Revision as of 21:41, 14 October 2024

What is going on in Gaza is atrocious beyond precedent. Never before, in the history of mankind, have such crimes been committed so openly, under the nose of the so-called International Community, over such infinite periods of time and with such steady progress in redefining the limits of barbarism.

In the face of History as a whole, the reason has less to do with the specifics of the tragedy than with the circumstantial fact that nowadays, with technology turning everybody into a top-equipped journalist, everything is known, captured in high resolution at a high repetition rate, and broadcast within seconds around the globe. Something similar happens in the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war, where one can see soldiers grilled alive in a tank or chased by a drone around an obstacle before the ineluctable embrace of death once the exhausted target, begging for his life, can't catch up anymore with the remote camera buzzing over his head with its grenade ready to detonate. If it wouldn't be disgusting enough, people enjoy putting hard rock music to accompany this entertainment from hell.

So while I am sure that barbarism has enjoyed tremendous peaks of creativity in the unspeakably nefarious History, for the first time, we have access to it in essentially real time, as if we would be there, except that we are on the other side of a screen, mere moments after it took place. With technology progressing hand in hand with barbarism, it won't be long before we can see all that live, round the clock. And the realism, the amount of details leaves us no escape and permits no looking away.

In the face of contemporary History, the difference between Gaza and the other ongoing live horror shows, is that, instead of soldiers who, even when unarmed, still have a military outfit, one is witnessing the martyrdom of a civilian population. And instead of adults, who, even when collateral victims, still bear the weight of suspicion and original sin, one is witnessing the sacrifice of innocent children.

The innocence of children...

Whatever the reasons, the context, the before and priors, in any circumstances, they are innocent. Harming them in any way is unbearable to anybody with a drop left of empathy in their dry soul. Harming a child is spitting in the face of all that is most holy. God to religious people. Your own children. Yourself in your memory of being a child if you have none. Even people who have no children once have been one. Everybody had access, even for a fleeting moment, to this purity, to this perfect sanctity that is childhood, to this bond of one's nascent consciousness with the Universal, with the greater beyond, with purity in its purest pure form.

Atrocity already reaches its paroxysm with the mere sight of those children shaking in fear, not understanding, begging, crying, calling for help and comfort, in pain not of their lacerated flesh but of the loss of their siblings, mother, father and all notion of good and evil... The fear, the terror, the incomprehension in their revulsed faces, their supplications, their agony... All this is draining me like a shortcut to the soul, connecting the figment of my self-respectability to the gutters.

Killing children...

Torturing and killing children is the ultimate abomination. There is nothing more vicious, wicked, evil that I can think of. This is stretching the limits of where forgiveness and remission can heal, this is jumping over the precipice that separates the brute from the beast.

Now, in Gaza, this is going on, and on, and on, from one day to the next, for weeks, for months, for years, every day, on, and on, and on.

And we only have to open the window of our desktop machines to see it, in front of us.

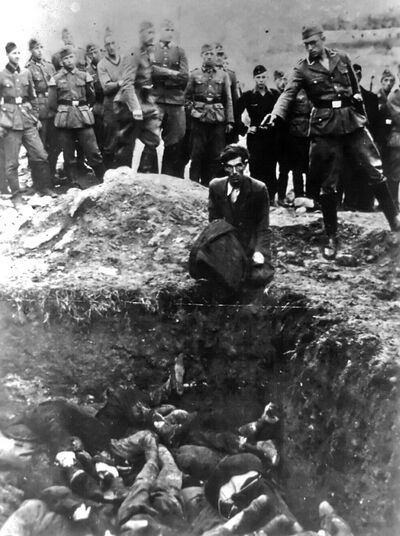

From previous deep dives of History into sheer horror, we only have still shots. Here is the famous picture "The last Jew in Vinnitsa", depicting the Einsatzgruppen executing a civilian in front of an open-air mass grave:

This image is chilling. It has haunted me since I was, myself, a child. I spent hours, at various stages of my life, trying to understand ourselves—human beings—in the expressions immortalized during this fatal split second.

The victim, first, holding his coat, maybe not to dirty it. His expression is inscrutable. The gaze is both distant and already in the afterlife, at the same time as it seems to anchor onto someone, something, a tree maybe, the roof of his house, more soldiers like those behind him. What is he looking at, like this? The incredulity of being one of us? I like to think he's looking at an Angel that only him can see, being already on the other side, and that his expression is one of embarrassment at having to embrace the divine from such a pathetic entrance: «Sorry». One can feel all the guilt of humanity on his expiating shoulders. Things that cannot be explained can sometimes be evoked in the prose of great authors. This mysterious expression always reminded me of Garcia Marquez's opening line to his Cien años de soledad: «Muchos años después, frente al pelotón de fusilamiento, el coronel Aureliano Buendía había de recordar aquella tarde remota en que su padre lo llevó a conocer el hielo.» His smile is tortured, floating between abnegation and acceptation. Maybe he does not believe what is going on, although he has just seen with his own eyes the others preceding him, roll down the pit after being shot. This is all just so absurd, that surely the frightful misunderstanding will be lifted. I think he is definitely looking at an Angel. Or remembers some suspended eternity once shared with his dad.

After trying to feel being him, in front of the grave that will punctuate his life, I then try to feel being the soldier about to execute him. His steady, precise position—straddling the precipice which he is about to fill with a human soul—the care in aiming precisely at the centre of the skull, the suspended breathing before pushing the trigger, the delicate concentration as if pondering a tricky task. The whole pose would look natural if he had a balloon to pop at the fair in front of him. It would already be chilling if it was a goose at his feet. But in front is this enigmatic, fathomless, infinitely precious soul who surrendered his fear, his rage and his torments to expose naked his fate to his murderer, becoming immortal together on this one instant that they both did not even live through and that is for us, instead, to spend the rest of our lives with.

And then the people behind this macabre couple... I always had a fascination for these photos where the victim is placed together with their assassin, side by side. This is the climax of vulgarity. Here the composition goes so far as merging them in the act, more intimately binding themselves together than two lovers. The incongruity becomes Christic. But back to the crowd, to the rest of humanity, to each one of the people behind them. One after the other. With their expression which is the one each of us still has, to this day, when we find ourselves, as Dard put it, less than the accomplice but more than the witnesses, of the crimes being committed, constantly, all around, by all of us, when they are committed by even the worst of us.

Look at these expressions... of resignation, disdain, puzzlement, disbelief, macabre curiosity even, revulsed interest probably. There is all of humanity in those faces. Not surprisingly. This is indeed humanity in its most faithful form: looking at the crime with swinging or crossed arms, one hand in the pocket, waiting for it to get through, and waiting for the next thing, for what comes next. What next? What after that? What have these people planned for the rest of their day in Vinnitsa?

This is us looking at the children of Gaza.

We are all in the picture. Elena does not let me evoke the topic of war, ever, neither in Ukraine nor in the Middle-East nor anywhere. She gets sick, stands up and goes away. She interrupts, she sighs, shakes her head and goes to attend to our girls, playing in the next room.

Look at the picture. She is there too. Some soldiers are looking away. One is already leaving.

Now this one picture is symbolic of the atrocities of distant times, far enough that even my father was not yet then born, and he is already gone.

Compare this to what we see nowadays. As I write this. There are no comparisons. I could look, since my teen ages, at this very picture, look at it in the eyes, in the eyes of the Picture, that is, not in the eyes of the people there, as nobody is looking at the Camera. There is no fraternity, no alleviation in one another, even through time. Everybody is alone in this picture, as we are ourselves when we look at it.

I cannot look more than perfunctorily at the dreadful images that arrive in a constant flow from Gaza. when I thought I had seen and read everything regarding the rest of the World, those who do not share my roof or my name, or my blood, that I had conceived all that is conceivable for humanity as a whole, that I had imagined all that I could try to regarding society, and found a way to cope with the misery of our cruelty, our selfishness, our brutality, to balance it with all that is beautiful, and hopeful, and clumsy and innocent... it all collapses with Gaza.

What happens in Gaza, goes beyond all that is humanly bearable.

The children split open with their guts and/or their brains gone, with bits still hanging from the fractured bones. The children with their limbs missing, torn apart, shredded. The children hanging from rubble. The children beheaded, burnt alive, split in two... The children covered in blood, covered in gravel, discolored in all the palette of death, from milky brown to blueish green, painting their angelic faces which they left on Earth as our own children leave theirs in the bed, when they fall asleep: silent, peaceful, gone. Gone for the night or gone forever.

Unlike "the last Jew of Vinnitsa", I cannot reproduce these images here. They are, in the most literal sense of the term, unbearable. They are a negation of everything that is acceptable or even conceivable: they are beyond medical or graphic or journalistic, or testimonies. They are so gross, so profoundly and completely ufpucking (I had to invent a word as I don't know what to put here), my subconscious and cowardice intimate me that they are fake. I lapse a second in the alternative that they are real, and I feel murderous myself, trembling and ashamed and guilty and scornful and angry at everything and everybody.

The revulsion comes from deep inside. It's probably not even the pictures in themselves. I never had any interest in gore as an artistic expression. I know some people feel attracted to the cinematic style, probably fighting their inner revulsion. To me, it just looks stupid and poor taste. I would get bored more than anything else. It is not the butchery mix of meat and bowels and blood that revulses me. I could probably stand a graphic image of a natural catastrophe spreading dismembered bodies around. In fact, probably not. I admire medical doctors largely for their ability to look at bowels and still see a human being. But still, beyond my girlish sensibility, it is really the notion, the knowledge that those are crime scenes, that mankind, that me, someone like me, the soldier propelling the last Jew of Vinnitsa in humanity's hole with a bullet, is committing and celebrating a sacrilege. The incongruity is beyond physical, it is spiritual, it is cosmic. If someone can do that, if an army, regular soldiers, can do that, then so could I. So could you. So could we. Humanity is the guilty party here, looking at the crime as if not pulling the bullet could be atoning for it. What happens in Gaza today shows us that it is not those who were kneeling in front of the mass grave of Vinnitsa who could say the contrary. We are all in this bloody mess together.

There is no need to discuss the context, the reason, the "politics" (what an obscene word in this context), there is no need to argue one way or the other, to justify or atone or explain or debate. Those are universal, timeless, inescapable, imprescriptible crimes. Those that we witness in Gaza are furthermore even more nauseating in that they have no precedent in the History of mankind. Conjonctural, maybe, surely. But still, never seen before, never so closely rubbing us in their unravelling. This is a new record in the book of atrocities. We managed to find a new way to meddle everybody in it.

Some people express concern, voice their outrage, point a finger. Those are people murmuring to each other from the back rank of onlookers in the Vinnitsa photograph. Anybody not jumping in the hole, not sitting by the side of the victim to receive the bullet first, is sharing the guilt of he who will trigger the rifle.

We are all guilty. We are all cowards, pathetic, disgusting pieces of shit shat by the devil on the open and bleeding wounds of children. Those who say nothing too, their silence is deafening in the turmoil and murmurs of those who discuss the how and why of what goes beyond words. Nobody is exempt from the great trial: "what would you do if faced with the ultimate atrocity, with the most abominable injustice, with the grand-final crime?"

The atrocities against the Gazan children are, literally, the worst crimes humanity has been directly and collectively committed to, in that they involve, one way or the other, everybody else, because they splash blood at all of us in particular, and at humankind in general. Previously, History had the decency to implicate us a posteriori, to let us have an escape window (If I had known!), to put a veil of distance and fuzziness on the graphic reality, to let some time and details pass, but not anymore. It now compels us to drink our morning coffee, to greet each other, to discuss Science or the weather, with this documented, ongoing, vivid and visual series of crimes accompanying us on a daily, on an hourly basis. To live as if all this was not happening. To pretend. And, if alluding to it, in a way that cannot concentrate more outrage than if we were to lament having missed the morning bus.

This is a new low for humanity. And we keep digging.