mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

<youtube width=278 height=276>TLKobnoXBTI</youtube> | <youtube width=278 height=276>TLKobnoXBTI</youtube> | ||

This text puts in verses what meaning one can find in existence: the one we attribute to it. We decide if the token of Dulcinea is the | This text puts in verses what meaning one can find in existence: the one we attribute to it. We decide if the token of Dulcinea is the rag used to mop the floor or a thin veil of gossamer. We value if the barber's hat is his shaving basin or the golden helmet of Mambrino. We see Dulcinea or we just see someone, whomever, Aldonza... The original has beautiful lines, such as {{onlinequote|To be willing to march into Hell for a Heavenly cause!}}, but Brel's version gets closer to what became the Quixotic ideal, to the ultimate vision that even Cervantes did not fully ignite, when he set fire to literature. Brel darkens and humanizes it profoundly. It leans into fragility, excess, despair, and yet stubborn persistence, all embraced by poetry. Those are the French lyrics: | ||

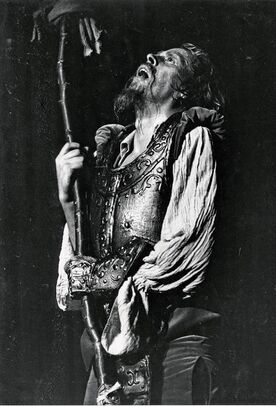

<wz tip="Brel as Don Quixote. Unfortunately, no complete recording exists of the whole Brelian scenic interpretation, only of the songs.">[[File:Brel-Quichotte.jpg|276px|right]]</wz>{{quote|<poem>Rêver un impossible rêve | <wz tip="Brel as Don Quixote. Unfortunately, no complete recording exists of the whole Brelian scenic interpretation, only of the songs.">[[File:Brel-Quichotte.jpg|276px|right]]</wz>{{quote|<poem>Rêver un impossible rêve | ||

Porter le chagrin des départs | Porter le chagrin des départs | ||

Revision as of 10:44, 15 February 2026

I have been immersing myself over the path few months into themes of human disconnection, where art amplifies rather than resolves inner voids.

Art is to communicate something, right? What does it achieve that other, simpler forms of communication—more economical ones too—can not?

If I want to tell you something, should I just not spit it out? Why try to make it beautiful too?

Why would I even have anything to tell you, in the first place?

Isn't any form of personal expression, isn't anything intimate we want to say a pompous way of pretending to hold a position of invulnerability that can't possibly be real? Why shout your thoughts at an anonymous collection of strangers? What could they possibly care, beside some morbid gossipy curiosity? This seems to be a complete mystery.

I believe some of these mysteries have been pierced by Cervantes, when he invented nothing less than the concept of the novel. He made this most daring and most important artistic step of humanity's intellect, to put a foot into reality through the window of his dreams. Alonso Quijano becomes Don Quixote. Aldonza becomes Dulcinea.

In some contemporary adaptations of the story, those themes have been well identified and articulated, prominently in the musical The Man of la Mancha of Mitch Leigh and Joe Darion.

This in turn inspired various adaptations worthy of interest, including the poorly received 1972 movie with Peter O'Toole and Sophia Loren. More importantly, it interested Brel enough that he bought the rights to produce the French version of the musical. There are few instances of major authors placing themselves in the shadow of another creator, in order to translate or adapt their work. Those include Borges translating Oscar Wilde and Kafka, or Nabokov translating Pushkin. In such cases of a giant transposing a monument, the translation always adds to the original. This is even more so the case with Brel, whose translations transfigure the already momentous work. The famous keynote song from the musical—The Impossible Dream—becomes, in the hands of Brel, one of his most beautiful texts and one of his most poignant songs: La Quête.

This text puts in verses what meaning one can find in existence: the one we attribute to it. We decide if the token of Dulcinea is the rag used to mop the floor or a thin veil of gossamer. We value if the barber's hat is his shaving basin or the golden helmet of Mambrino. We see Dulcinea or we just see someone, whomever, Aldonza... The original has beautiful lines, such as «To be willing to march into Hell for a Heavenly cause!», but Brel's version gets closer to what became the Quixotic ideal, to the ultimate vision that even Cervantes did not fully ignite, when he set fire to literature. Brel darkens and humanizes it profoundly. It leans into fragility, excess, despair, and yet stubborn persistence, all embraced by poetry. Those are the French lyrics:

Rêver un impossible rêve

Porter le chagrin des départs

Brûler d'une possible fièvre

Partir où personne ne part

Aimer jusqu'à la déchirure

Aimer, même trop, même mal

Tenter, sans force et sans armure

D'atteindre l'inaccessible étoile

Telle est ma quête

Suivre l'étoile

Peu m'importent mes chances

Peu m'importe le temps

Ou ma désespérance

Et puis lutter toujours

Sans questions ni repos

Se damner

Pour l'or d'un mot d'amour

Je ne sais si je serai ce héros

Mais mon coeur serait tranquille

Et les villes s'éclabousseraient de bleu

Parce qu'un malheureux

Brûle encore, bien qu'ayant tout brûlé

Brûle encore, même trop, même mal

Pour atteindre à s'en écarteler

Pour atteindre l'inaccessible étoile.

What a transfiguration of the original! This looks like dipping fine prose into pure poetry. The vow—«Aimer, même trop, même mal», that literally translates as «To love, even too much, even badly»—in itself is an absolution for anybody to do anything. As long as they do it to fulfil an ideal of devotion, of admiration, of love. It absolves the timid, the ugly, the sick, the old and the forsaken, from laying eyes on a princess. You do not aim at reaching the star, you merely try to. And that is enough. And that is everything. It is the alchemist's miracle of turning the mud of this world into a treasure, of turning indifference into admiration, resignation into courage, sarcasm into faith... the list is unending. You become a magic wand that can turn any insult, any shortcoming, any vice into a virtue. When you have this fire inside you, when you declare you are no longer Quijana (the name is different in the musical) but Don Quixote, you become more than yourself. That is the first purpose of communicating through art. You speak to yourself, first and foremost. By saying to the world «Listen to me», you then have to say something—«Poor world, unbearable world, It is too much, you have fallen too low»—and then you have to say what this artistic impudence entails: «Listen to me, A Knight challenges you». And that's it, you became a hero, dragged by the prose, word by word, towards an epic story.

Écoute-moi

Pauvre monde, insupportable monde

C'en est trop, tu es tombé trop bas

Tu es trop gris, tu es trop laid

Abominable monde

Écoute-moi

Un Chevalier te défie.

The other purpose of art is beauty. And the greatest beauty of all beautiful things resides in someone's way of looking at the world, and you looking at them. I believe so. Although it is not the case in the novel, the tension around what might arguably be the most universal of themes—love—has been brought to the fore in the musical, and is the best aspect of the movie since Aldonza is played by a very Dulcinesque Sophia Loren, who rebukes a hopeless but resolved Peter O'Toole:

This is the main theme of the musical (not of the novel): the contagious spread of hope, the elevation of those who listen to it and enter the story—become the story—along with the one who is making it up. This is when art becomes communication: the narrative becomes a dialogue. Aldonza finally trusts that she is Dulcinea. When Quijana dies, she corrects Sancho who addresses her as "Aldonza", saying that she is, truly, Dulcinea. There lies another answer to our earlier questions. The morbid curiosity, the gossips of the collection of strangers is there too, of course—it is everywhere—but the glory is not for them, and in their chorus mocking the ballad of the knight, they actually also end up making up something, although clumsy, that is beautiful. The transformation of the world is complete.

But glory is, like the star in the sky, punctual only. Another interesting modernization of the novel is through the knight of the mirrors, Carrasco—both the brother in law and, ultimately, the Knight of the White Moon in the novel, the one who defeats Don Quixote—but who in the musical becomes a more symbolic and effective metaphor for "truth" or "reality", shattering the power of imagination, or, more accurately, conviction. This reflects art as fabrications and deceits. Those mirrors are tainted with the colors of the deriding vocabulary: histrionic, melodramatic, pompous... This is how you kill a knight-errant, scorning him as a buffoon, mocking him as a pathetic loser. That is deadly to him because that is true. This is what makes him fall from his horse and his universe onto the harsh ground of reality. This is also how you kill an artist, by telling them: "I don't see you", "I don't feel you" or, worst of all, "I don't believe you."

So yes, art and reality are two different things. And probably, we have to decide between them. I would digress too much if I were to start discussing which of the two is really "real".

Thus, a pompous way of pretending to hold a position of invulnerability that can't possibly be real? Yes, definitely! What could be more pompous than to think yourself—a mere hidalgo—as a knight, as the noble "Don Quixote", let alone, of la Mancha, because you wanted «como buen caballero, añadir al suyo el nombre de su patria y llamarse "don Quijote de la Mancha", con que a su parecer declaraba muy al vivo su linaje y patria, y la honraba»?

The position of invulnerability? Yes, definitely!

Trop faible?

Qu'est-ce que la maladie?

Qu'est-ce qu'une blessure pour le corps d'un chevalier errant?

A chaque fois qu'il tombe, voilà qu'il se relève et malheur aux méchants!

Can't possibly be real? Yes, definitely!

Les géants tremblent déjà

Va-t-en réduire en confiture

Tous les moulins à bras de La Mancha

Par ta triste mine, par ta triste armure.

Does someone care? My anonymous collection of strangers, don't you? It doesn't matter if you do; let alone that, not being Cervantes, I can't communicate much anyway, and that I never wrote anything. I am too humble to worry about morbid gossipy curiosity, but if you want some, here we go. I once told an Aldonza, a long time ago, some of the things that an errant-knight would read in the sky, by the moonlight. I got a variation of the same feedback they all get:

Of all the cruel devils who've badgered and battered me

You are the cruelest of all

Can't you see what your gentle insanities do to me?

Rob me of anger and give me despair.

But isn't this part of the journey of any quest to the unreachable star? Isn't it, maybe, the whole point? «D'ailleurs qu'importe l'histoire... Pourvu qu'elle mène à la gloire !» And the insanity of the errant-knight gives him the strength of never being defeated. One time, somewhere, somehow, despite all the pedantry and the petulance, and although I have to conjugate this in the future perfect, I know that I once will have made one Aldonza doubt whether she was not—after all—Dulcinea. It also doesn't matter if I am right or wrong.

Why does he live in a world that can't be,

And what does he want of me?

Why does he say the things he says?

Why does he say these things?

"Sweet Dulcinea" and "missive" and such,

"Nethermost hem of thy garment I touch."