No edit summary |

m 1 revision imported |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 19:43, 14 February 2026

Quantifying Quantum Coherence in Polariton Condensates. C. Lüders, M. Pukrop, E. Rozas, C. Schneider, S. Höfling, J. Sperling, S. Schumacher and M. Aßmann in Phys. Rev. X Quantum 2:030320 (2021). What the paper says!?

This work studies polariton condensation and the buildup of coherence:

we observe the transition from an incoherent thermal ensemble to a state that carries a significant amount of quantum coherence

but from the quantum coherence lense of quantum resource theory. As such, this studies the problem of «classical-to-quantum transition». What they really do is

we study phase and intensity fluctuations of the polariton condensate

They do that theoretically (with the truncated Wigner approximation) and experimentally.

There is a rather pretentious claim at hybrid interfaces for multidisciplinary quantum prospects

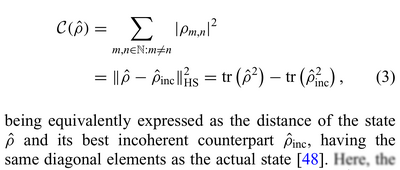

Their main quantity is the "quantum coherence":

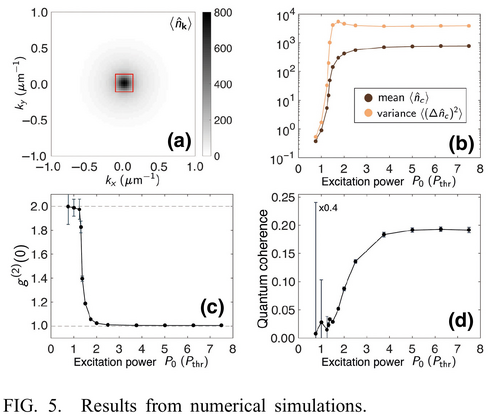

Their main (interpretation-free) results:

1 - theory of coherence buildup:

2 - experiment of coherence buildup:

Referring to our work:[1]

the above works did not employ a unified concept of quantumness and focused on transferring quantum features of the pre pared nonclassical light to the semiconductor system, not probing the coherence properties of the matter system itself via the emitted light as we are going to demonstrate here.

They recognize that for light, coherent states are classical and quantum properties are evidenced by quantum correlations:

While entanglement in hybrid systems is certainly useful [31], other forms of quantumness can exist beyond entan glement [2,32–34]. For instance, a classical electromag netic wave is most closely resembled by what is known as a coherent state, resulting in phase-space descriptions as introduced by Wigner, Glauber, and others [35,36]. And correlation functions can be used to discern classi cal wave and quantum particle properties, as observed for single photons [37].

But for matter, this is the opposite:

However, matter does require a dif ferent classical reference in which the wave properties are identified as quantum features and particles are the classical default, rendering commonly applied correlation function-based and phase-space approaches to identify nonclassicality less useful.

Here too, they recognize that their approach is non-standard:

In this work, we specifically consider a superposition of particles to represent quantum phenomena in matter systems. This is in contrast to the standard concept of nonclassicality of light in which photons themselves, i.e., particles of quantized waves, are deemed highly nonclassi cal objects [38].

Later they come again to the fact that coherent states are classical:

Coherent states resemble classical oscillators most closely; thus they serve as the classical reference for waves but identify quantum particles as nonclassical [55,56].

Regarding the status quo on this, they come back to "matter systems" being special:

Specifically, the inconsistency of P with a non-negative probability distribution defines nonclassical radiation fields in quantum optics. Here, however, we want to iden tify particles as classical in order to provide a characteri zation of the matter system.

The juggling is dizzying:

Historically, matter has been understood as a collection of particles. Consequently, they here serve as the classical gauge for determining genuine quantum features in matter in the form of their super positions. Thus, we ought to employ number states $\ket{n}$ as our classical reference [Eq. (2)].

Everything means one thing and its opposite:

In general, nonclassicality in the quantum-optical sense and quantum coherence in the number basis are comple mentary notions. That is, a Fock state $\ket{n}$ exhibits quantum signatures in the former sense but is classical in the latter context, and vice versa for a coherent state $\ket{\alpha}$

Here, they basically say that if you want something quantum, just find an interpretation that makes whatever you have "quantum":

The elementary examples above, in which different states are deemed quantum through different approaches, demon strate the fundamental distinction between the common notion of nonclassicality and the operational concept of quantum coherence for quantum information.

The laser is quantum then?

the laser, producing coherent light, has been one of the first commercial appli cations of such quantum superpositions

There, they refer to catalytic coherence, which looks interesting.[2]

They also come back to this in their conclusions:

In our matter system, particles represent the classical reference and their superpositions define quantum effects, unlike for electromagnetic waves where bare photons are already considered to be nonclassical. Therefore, com monly applied quantumness criteria for light cannot be applied to witness the quantum features of a condensate. Rather, polariton superpositions are encoded in the super position of photon-number states.

First part of the sentence is unclear ("we probe for sophisticated particle quantum coherence effects"), they defy frequently-held belief:

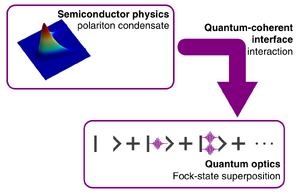

Thus, we probe for sophisticated particle quantum coherence effects within a polariton condensate via Fock-state superpositions in the emitted light field that carries the information about the matter system; see Fig. 1. Thereby, the frequently held belief that only Fock states are resourceful is defied, which is additionally supported by applications, such as quantum random number generators [39,40] for quantum cryptography [41] and entanglement detection [42], that can be carried out with coherent laser light.

Their refs [39-42] should be studied to identify what(if it) goes wrong.

Because it concerns off-diagonal elements, it is complementary to $g^{(2)}$ characterizations:

Quantum coherence may thus be considered as complementary to earlier approaches in condensed-matter systems. While the buildup of macro scopic coherence and $g^{(2)}$ in polariton systems has been widely investigated [44–47]

Ironically, although they make this confusion, they say coherence is not the same in quantum resource theory than it is in quantum optics and condensed-matter physics:

The quantum-information-based concept of quantum coherence must not be confused with the notion of macroscopic coher ence that can have a classical or quantum origin and that is frequently used in semiconductor physics.

Their description around Eq. (1) is wrong («off-diagonal entries can be used for implementing quantum protocols»), that around Eq. (2) is correct (mixed states are classical)

This is also wrong:

They compute quantum coherence for the displaced thermal (cothermal?) state.

Their statement that "quantum coherence" leads to entanglement (right column page 5) should be scrutinized. They might be merely saying that coherent drive of nonlinear system can produce entanglement.

They compute (numerically) $g^{(1)}(\Delta r)$ and finds it increasing with pumping, which shows phase buildup, but they add:

(1) Importantly, g is not a quantitative measure. It certainly provides a length scale over which phase cor relations are preserved. But it cannot yield any additional information about the quantum nature, or lack thereof, of the state.

They don't actually measure the phase:

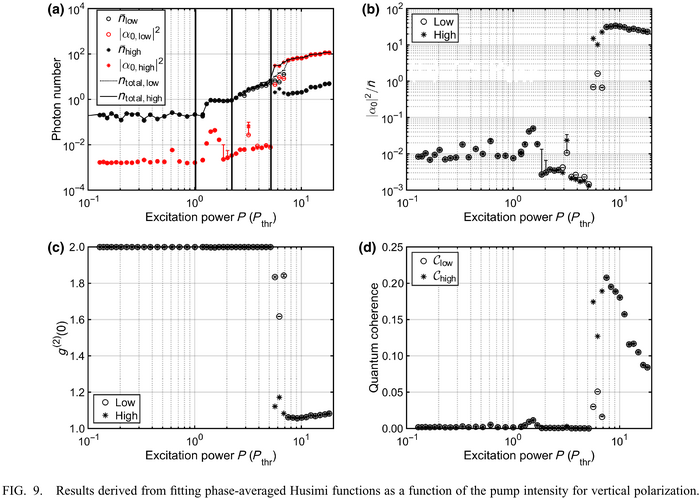

As the phase of the sample light field fluctuates on a timescale of 100 ps, given by its coherence time, there is no long-term phase stability between the signal and the LO. Therefore, in a measurement that takes several hun dred milliseconds to accumulate enough quadrature values, we average over all phases between signal and LO and receive a phase-averaged version of the actual Q function. The phase information could be obtained by employing more homodyne channels and reconstructing the relative phase between them [79]. However, the phase-averaged Q function already provides the necessary information since Eq. (6) requires only n̄ and $\vert\alpha_0\vert^2$, but not the phase arg α0.

They also repeat that in the conclusions:

In addition, our current experiment is not able to resolve the phase, resulting in phase-averaged Husimi functions of displaced thermal states. But our sim ulation of correlation functions for the polariton system directly implies that this averaging does not describe the true state. Thus, a targeted improvement of our setup is enabling a phase-resolved measurement in the future

In addition of all the basic physics, they also describe bistability instabilities resulting in jumps of their $g^{(2)}$ (see Fig. 8).

References [58, 84-86] should be studied there because they make this dubious claim critical:

Finding quantum coherence in the polariton condensate is significant as it, for example, renders a conversion into entanglement and other quantum correlations possible [58, 84–86]. As such, the measured quantum coherence is an operationally equivalent quantum-computational resource as entanglement [3,4,9] [...] That is, the superposi tions of Fock states can be transformed into entanglement without requiring coherent processes where the amount of output entanglement is identical to the input coher ence [58].

There are various thought-provoking, if not grandiloquent and petulant statements, such as:

in today’s research, semiconductor physics and quan tum optics increasingly become separated fields, departing from their common origin.

As well as a tiring constant shoving that this is multidisciplinary work (maybe to please a Referee regarding criteria of the journal).

References

- ↑ First observation of the quantized exciton-polariton field and effect of interactions on a single polariton. A. Cuevas, J. C. López Carreño, B. Silva, M. De Giorgi, D. G. Suárez-Forero, C. Sánchez Muñoz, A. Fieramosca, F. Cardano, L. Marrucci, V. Tasco, G. Biasiol, E. del Valle, L. Dominici, D. Ballarini, G. Gigli, P. Mataloni, F. P. Laussy, F. Sciarrino and D. Sanvitto in Science Advances 4:eaao6814 (2018).

- ↑ Catalytic Coherence. J. Åberg in Phys. Rev. Lett. 113:150402 (2014).