Bluebeard

Bluebeard is a 1987 novel by Kurt Vonnegut on artistic expression, on what is art and what is not, on why someone able of photographic realism may choose to rely instead on the most basic simplification, and, overall, the interplay of truth, depth and meaning in one's Work, which, for the artist, has to be a testimony, without which the work «has no soul».

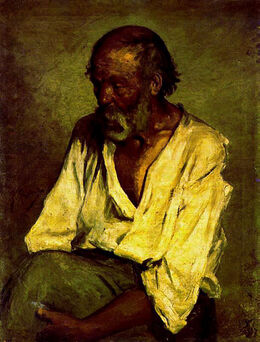

Vonnegut chose painting—although the theme applies to him as a writer—mainly because this is the discipline that best articulates the contrast between what is meaningful from what is impressive but superficial. The contrast can be so strong that both the Author himself as well as the main character, remain throughout dubious of the real worth of abstract Art. For the reader too, the dispute between realism and abstract painting is a straightforward way to put into perspective the opposition between skill and expression. Everybody indeed wondered at some point if there is real genius in Miró or Mondrian. The novel's main point could be expressed as (but isn't): "If Picasso can paint The Old Fisherman, why does he paint Femme assise au chapeau de paille? The protagonist, Rabo Karabekian, meets Picasso in the novel, but only to have him close the door to his face. Some questions can never be answered, not even to those who could understand.

Rabo's most famous piece—Windsor Blue Number Seventeen—is similarly a gigantic series of uniformly painted canvas, «straight from the can». The question of what this is worth is resolved in the novel when Rabo makes a portrait of his two boys, asleep in front of the fireplace, to silence the critics of his wife, who is flabbergasted by the quality of his realistic drawing. When asked why he would not always use his tremendous skills as such, he replies:

It’s just too fucking easy!

This famous tension repeats in the novel, such as when Rabo draws with his thumbs a realistic rendition of another suspicious critic. To make it clear that technical prowess has no value, he immediately covers it, after having made his point, under his original (abstract) painting, below a uniform background. Even the title is named after the paint. Interestingly, though, the drawing will be what eventually remains of the confrontation, after his original Art self-destroys due to the use of "Sateen Dura-Luxe", a paint which turned out to later disintegrate. This afflicts in particular Windsor Blue Number Seventeen. The central theme is thus not only that of the importance, but also that of the permanence, of the Artist's Work. This is particularly salient in Vonnegut's work who, on several occasions, toyed with the Gogolian urge of self-destruction, for instance in Cat's cradle's final Calypso from the book of Bokonon, or in his Make your soul grow reply to high school students.

The notion that the artist has to be able to master the technique, to also be able to ignore it, still appears to remain necessary or at least relevant for Vonnegut. Both Rabo's Master, and himself, are gifted with the capacity to paint perfect copies of the original (the Master counterfeiting a banknote, Rabo painting a photo of his Master's studio). This will turn out to support the coup-de-théâtre, revealing the content of the potato barn, where Bluebeard hides his secret (whence the connection to the fairy tale). In there, hides all the horror, desolation and sufferings of the Artist's companions. Not his wives, in the case of Rabo, but his fellow humans. The universal, humanistic themes of Vonnegut thus remain central to the story.

Other interesting themes include the Armenian genocide, the good fortune of some people and their inability to control it, populism and feminism. The choice of title for Rabo's ultimate, all-embracing masterpiece, "Now It's the Women's Turn", is a brutal reminder of the latter's limitations.

Another major theme is the thin line between truth and fiction. The story is written as an autobiography. Many characters who contribute to the story did really exist, such as Pollock. Circe Berman, to whom the book is dedicated, is an interesting (fictional) character. Her not being a real person turns the dedicatory of the equally fictitious protagonist into an indication that everything that matters is, after all, true enough. She seems to represent a negative to all that Vonnegut was perceiving in himself as a writer: she is flamboyant, insouciant, immensely successful professionally yet not admired for her talent as a writer but for more substantial, direct and genuine qualities. Unsurprisingly, she is in constant confrontation with Rabo, who represents Vonnegut himself at a deeper level. She also charms and attracts him. She, finally, humbles him, prominently with the redecoration of the foyer. She is also the catalyst to force him to become or reveal himself. On her bad side, she turns out to be a lunatic as well as unable to transcend youths, whom she, instead, corrupts. She, therefore, represents literature. Rabo represents, in opposition, the human being.

Bluebeard is a masterpiece. The main theme as exposed above is that technical mastery is only that, and that what matters is what is human. The book could be seen as an annexe to Breakfast of Champions to explain the «unwavering band of light». The abstract, simple, pure neon light that Rabo sees underneath the realistic, complex, afflicted "meat" of living beings.

At the bottom of it is the selfish notion that what we feel in the course of our sufferings, of our "meat" and "soul" struggling in their afflictions, is what makes us human. We may, on occasion, be able to communicate a little bit of it to others. If so:

Oh, happy Meat. Oh, happy Soul. Oh, happy Rabo Karabekian.