The Visitor

The Visitor is a 2007 drama by Thomas McCarthy.

Tarek's mother on the way America treats immigrants.

![]() Walter Vale is a passive element of society, a university professor who doesn't do research anymore, occasionally co-authoring papers he just read and teaching only a single class under the pretext of working on a book on which he doesn't progress. When he is sent forcefully to New-York to attend a conference, he meets (in rather peculiar circumstances, but I know personally people who almost lived the same thing) illegal immigrants of Palestinian descent from Syria, whom he befriends. One of his escape route from his pointless life is music, for which he has no talent as far as piano is concerned, but he finds some solace in playing the djembe with his new acquaintance, Tarek.

Walter Vale is a passive element of society, a university professor who doesn't do research anymore, occasionally co-authoring papers he just read and teaching only a single class under the pretext of working on a book on which he doesn't progress. When he is sent forcefully to New-York to attend a conference, he meets (in rather peculiar circumstances, but I know personally people who almost lived the same thing) illegal immigrants of Palestinian descent from Syria, whom he befriends. One of his escape route from his pointless life is music, for which he has no talent as far as piano is concerned, but he finds some solace in playing the djembe with his new acquaintance, Tarek.

In the metro, one day, Tarek is controlled by the police and, having no ID, is brought to a detention center. Walter visits him regularly, assisting in the process of having Tarek released (he contracted a lawyer and met Tarek's mother, also an illegal immigrant, whom he shelters at his place).

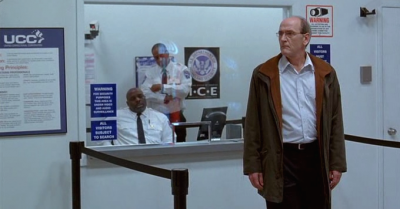

The apex of this movie is the fleeting transformation of this obedient, defeated, half-nice, half-despicable shadow of society into a furiously distressed human being, suffering emphatically for the injustice committed by an inhumane legal system to another human being, whose only crime is not to be admitted in this society, an alleged model of democracy. The moment when this happens is short, it's all embedded in a single scene, when Walters learns that Tarek has been "removed", which means, "deported", one morning, with no previous notification (to him who was visiting daily, or to his family), no warning of any sort, just like that, suddenly, Walter got an evasive phone message from his friend telling him that something's happening. Hurrying at the center, we witness the confrontation in the empty room between an extremely worried Walter and the agents of the legal and repressive systems, two officers, in their detached, calm, deadly stance, reciting the rules and the law to break loose a staggering news. The dialogue is icy, it has all that makes the British language and the American culture exaggeratedly politically correct in situations of extreme violence: "Thank you Sir, I appreciate it" says Walter when the officer makes him the favour of consulting his computer before the opening time, the sort of deference to authority that inflects it to do something trivially out of the ordinary. In the process, insisting through similar rhetoric, he learns of the fate of his friend. And after all the information has been flushed to him, tidied up in fake or vacuous civilities, with "Sir" going back and forth, the peak in violence from the legal system smashes back at him, still wrapped in meaningless cordiality:

- — I'm sorry sir, it's all the information that I have... Now please, step away from the window.

And here comes the transformation. We are familiar with this Step away from the window from previous visits, when the room was full, and a queue was lining up to receive disappointing or life-crushing news from the agent, or a permission, maybe, to visit the detainee. This signals the termination of the interview and that the next in line will now take over, something surely necessary as there too is someone suffering. Here, however, the room is empty, this is before opening time, nobody will show up anytime soon, Walter is alone in his pain and despair. And the legal machine stabs him, again, and again:

- — Sir? Step away from the window please.

Of course this inhumane, sadistic, blind, cruel, absurd order catches the audience and Walter by surprise. The few seconds he needed to gather his thoughts are shattered by this incongruous remark. This is a poignant illustration of a system enforcing its pernicious dictatorship, efficiently trained to get rid of problematic or useless elements, concealing its abuse of mankind under the pretence of law and order, under the cover of legality, of legitimate authority. Naturally, there is always some nice draping to it, "You can contact ICE if you have any further question. The number is on the wall." but still the escalation:

- — Sir. For the last time. Step away... from the window.

Here we see Walter stepping away from the window, completely at loss, stunned by the violence of this polite encounter, the system having decided at this point that he was annoying, had exhausted all its rights and is now being threatened, under the empty look of the two agents in uniform behind their window.

We see him evasively looking around, he will even aim for the wall, have a look at the number there, realize it is completely useless, and then explode, let his rage, beautifully humane, fight back and express itself. The officers remain unconcerned, maybe toying with the idea of arresting him. This won't go much farther. The character will recede into his futile life of going along with the rest of the world as we find it.

The movie is a masterpiece on many accounts. Primarily, it is a real critics of society at large, and how we treat our equals on the basis of vague or obsolete political notions, on what is our personal involvement and stance in front of the injustices committed to others. It is also a refreshing and courageous look at American society itself and how it deals with minorities and human rights, which is, badly and shamefully. It conveys a deep message on the futility of life and how this becomes bearable through interactions with other people, illustrated with the little things that happen between the characters (Walter, Tarek's mother and girlfriend) when not directly related to him, like a boat trip, going to the opera, having a coffee. This feeling would also apply in the case of the terminal illness of some beloved one or any trauma that would make life pointless. It is here very nicely explored and put in perspective. Not least, it also avoided a pathetic love story between Walter and Tarek's mother, or a fake outcome like a wedding or some sort of arrangement to fix the case. No, everything is destroyed, the lifes of these people are ruined, Tarek is deported, his girlfriend is torn away from him and forever lost (either because she will be deported herself but to Senegal, or live in continuous fear of that in the States), his mother also leaves her life to go back to Syria, and Walter goes back to his previous life, only with a little bit more of harmless rebellion, illustrated by his playing the djembe in the metro, a trait of defiance shared with a friend more quickly lost than made.

See also

- The officers of the immigration center are perfect examples of "citizens" and the protagonists of "technical slaves" as defined by Traian in the twenty-fifth hour.